What Is Trauma?

Trauma isn’t just a psychological experience. It affects the entire human organism: the nervous system, the brain, the body, relationships, identity, and even how future generations respond to stress. Research from neuroscience, attachment theory, and trauma specialists such as Bessel van der Kolk shows that trauma leaves traces not only in memory but in our physiology, behaviour, and the ways we relate to others. It can shape the beliefs we form about ourselves and the world, sometimes without us even realising it.

In therapy, I often meet people who are carrying both their own wounds and the unspoken echoes of the people who came before them. Many have grown up in families where stress, shame, fear, or survival-mode coping were simply “normal.” When you understand trauma through this wider lens—biological, psychological, relational, and generational—healing starts to make more sense. We’re not just dealing with what happened, but with how our mind and body learned to adapt. That understanding helps make therapy feel safer and the healing more sustainable.

Disclaimer

I wouldn’t call myself a trauma therapist, but I do work in a trauma-informed way. This means I’ve educated myself enough (and continue to keep learning) to understand how trauma might show up in the therapy room and how to work with it gently, safely, and without risking retraumatisation. At the bottom of this post, I’ve shared some of the resources that have supported my own understanding. If you want to explore further, they’re genuinely worth a look.

The Window of Tolerance: Why Safety Matters in Healing

When we talk about healing trauma, we’re not talking about “thinking positively” or forcing ourselves to be rational. Trauma doesn’t get stuck in the thinking brain. It gets stored in the survival brain, which is the part that reacts before we can make sense of anything. This is one reason people can know they’re safe but still feel overwhelmed, frozen, or on edge.

Dr Dan Siegel’s Window of Tolerance is a helpful way to understand this. It describes the range in which we can stay regulated, connected, and fully present. When we’ve been through trauma, that window often becomes much narrower, and we can slip out of it very quickly.

Many survivors find themselves dropping into either:

- Hyperarousal: the body goes into fight-or-flight mode, leading to anxiety, panic, restlessness, anger, or constant scanning for danger

- Hypoarousal: the body shuts down to cope, leading to numbness, exhaustion, disconnection, or dissociation

Both states are protective. They’re the nervous system doing its best to keep us alive. But when they become our default, everyday situations start to feel unsafe, even when nothing is actually wrong.

Therapy aims to gently widen that window. And because trauma is held in the body as much as in the mind, the work often includes practices that help the nervous system relearn what safety feels like. Breathwork, grounding exercises, rhythm, gentle movement, and the experience of being regulated alongside another calm, attuned person—all of these help create the conditions for healing. As Bessel van der Kolk famously points out, many of the most effective trauma modalities come from community-based, embodied traditions: yoga, tai chi, dance, theatre.

At its core, trauma recovery isn’t just about processing the past. It’s about helping the body rediscover a sense of safety so that the person can live in the present again.

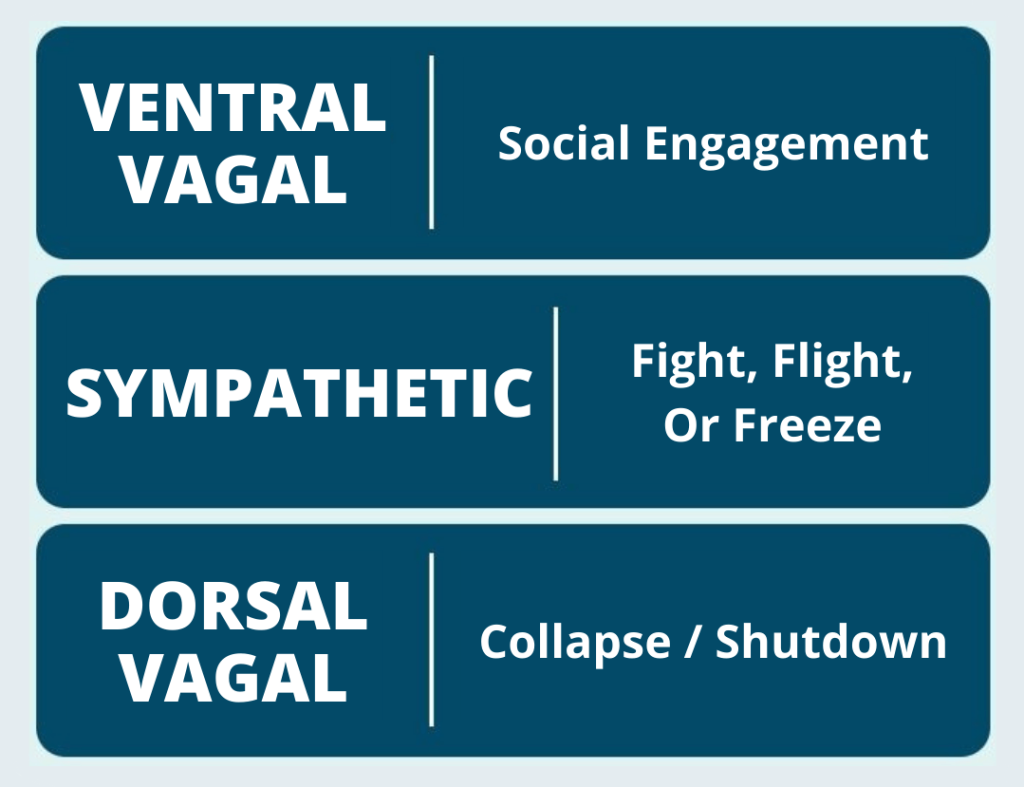

The Biology of Trauma

Once we understand how trauma narrows the Window of Tolerance, it becomes easier to see why the body responds the way it does. When something overwhelming happens, the nervous system doesn’t pause to let us think things through. It reacts instantly. We don’t choose our trauma responses; they happen before conscious thought is even available.

The survival brain steps in and activates one of several automatic responses designed to keep us alive. Most people know the classic four (fight, flight, freeze, and fawn) but the list can expand depending on the source. Some researchers add flop, faint, or friend/flock to capture the full range of human survival instincts.

The four main responses:

- Fight: pushing back, arguing, defending yourself, or feeling sudden anger.

- Flight: wanting to escape, avoid, shut down, or leave the situation entirely.

- Freeze: going still or numb, spacing out, or disconnecting from what’s happening.

- Fawn: appeasing, placating, or prioritising someone else’s needs to stay safe.

Additional responses:

- Flop: the body goes limp, almost like its energy drops out of it; a deeper form of shutdown.

- Faint: a dissociative collapse where the system temporarily switches off.

- Friend/flock: seeking connection or trying to “befriend” the source of threat as a survival tactic.

All of these are protective. They’re not choices, weaknesses, or personality flaws. They’re reflexes.

During extreme threat, the frontal lobe—the part of the brain that handles reasoning, memory processing, language, and meaning-making—can temporarily go offline. This is why some people can’t recall parts of what happened, or why memories feel foggy and out of order. It’s not that someone “blocked it out on purpose.” It’s that the brain prioritised survival over recording the moment.

In other words: sometimes the body remembers what the mind cannot. And that’s not failure. That’s protection. It also means that trauma therapy doesn’t require remembering every detail in order to heal.

Because trauma reorganises the brain, people who’ve lived through it commonly experience things like:

- staying on high alert even when nothing is wrong

- struggling to filter out irrelevant information

- feeling unsafe in everyday environments

- disconnecting from bodily sensations

- repeating painful relational patterns without knowing why

Again, these aren’t personality traits. They’re the biology of threat.

Over time, chronic stress can even influence how certain genes are expressed. This is where epigenetics comes in. Trauma doesn’t change the DNA itself, but it can change how genes switch “on” or “off,” affecting things like stress hormones, immune responses, and emotional regulation. These shifts can be passed to the next generation, offering one pathway for generational trauma. It’s not inherited trauma stories, but it’s inherited physiology shaped by the environment our ancestors survived.

The Psychology of Trauma: How Patterns Are Passed On

If biology explains how trauma lives in the body, psychology explains how it travels through families and communities. Trauma isn’t inherited only through nervous system responses or epigenetic changes. It’s also passed down in the ways we learn to cope, relate, and make sense of the world.

Children absorb these patterns long before they have the language to describe them. If a parent deals with threat by shutting down, appeasing others, or staying constantly alert, children internalise these responses as “normal.” Not because anyone teaches it directly, but because children learn first through watching.

These learned patterns shape:

- how safe we feel with other people

- how we manage conflict or discomfort

- how we express or suppress emotions

- how much we trust connection, support, and vulnerability

Trauma is also shaped by the world around us. It never exists in isolation. The impact of any overwhelming event depends on the social and cultural context: poverty, racism, discrimination, access to support, community safety, and even how a society talks about (or avoids talking about) trauma. Two people can live through the same event but have entirely different outcomes depending on the resources available to them.

In childhood especially, trauma can influence brain development. It may affect self-regulation, learning, creativity, and the ability to form safe relationships. Research describes four possible pathways after traumatic experiences:

- enduring (symptoms persist)

- recovery (symptoms reduce over time)

- unaffected (little visible disruption)

- delayed (symptoms appear much later)

This range is normal. Children don’t all react in the same way, and many don’t show signs until adolescence or adulthood, often when stress or relationships awaken those earlier wounds.

But it’s essential to be clear: none of this is about blame. Most people parent using the tools they have, often shaped by their own history of survival. Recognising how patterns repeat is not about judging previous generations. It’s about noticing the impact with honesty and compassion.

This is how psychological healing begins. Every time we slow down, breathe, and respond with awareness rather than instinct, we shift the trajectory. Even small moments of choosing differently can interrupt a generational pattern that has been running for decades.

When Trauma Feels “Stuck”: Meeting the Inner Child

Understanding the psychology of trauma naturally leads to a deeper question: what happens to the parts of us that never got the safety, support, or language they needed at the time? This is where inner child work becomes especially meaningful.

Trauma doesn’t always show up as flashbacks or nightmares. Often, it shows up as younger emotional states resurfacing in adult situations. It can feel like we’re suddenly reacting with the intensity of a child or teenager, even though we know (logically) that we’re grown. That mismatch is a clue.

In my own therapy, I realised that the emotions bursting through in adulthood were almost identical to the ones I had felt as a teenager. Back then, I coped by striving for perfection, pushing myself harder, and hiding how overwhelmed I felt. Those strategies kept me afloat at the time. But as an adult, they turned into anxiety, exhaustion, and a constant sense of never being “enough.”

When my therapist gently asked, “How old do you feel right now?” something clicked. I wasn’t overreacting as an adult. I was re-feeling what a younger version of me had never been able to express safely.

This is the heart of inner child work. It’s not a trend or a gimmick. It’s a trauma-informed way of reconnecting with the parts of ourselves that were left behind emotionally, developmentally, or relationally.

And in practice, it’s surprisingly simple. Sometimes it looks like:

- naming how old a feeling feels

- allowing a safe person to witness your emotions

- writing letters you never send

- looking at old photographs and offering compassion to the child you were

- grounding that younger part with words like, “You’re safe now. I’m here.”

As those younger parts are met with care instead of fear, something changes. The intensity softens. The reactions that once felt overwhelming begin to lose their grip. Over time, those parts stop running the show. The old wounds become integrated memories rather than active injuries.

And this is where inner child work meets generational healing: when we tend to our own emotional younger selves, we break the patterns that trauma tries to pass forward.

Breaking the Cycle

Whether trauma began with you or with generations before you, the path toward healing moves in the same direction: awareness, compassion, and safe connection. We don’t undo the past by force or willpower. We soften it by meeting ourselves—and others—with understanding instead of judgment.

Every time you pause instead of react, breathe instead of shut down, or offer comfort instead of criticism, you’re already shifting the pattern. Trauma can be passed on through families, but so can resilience, empathy, and the capacity to grow. Healing never stops with one person. It ripples outward: into relationships, communities, and the generations that come after.

If you’d like to explore this further, here are some resources I often recommend:

Books

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk

- Trauma and Memory by Peter A. Levine

- The Body Remembers by Babette Rothschild

- The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy by Deb Dana

- Anchored by Deb Dana

Websites

- UK Trauma Council: https://uktraumacouncil.org/resources/childhood-trauma-and-the-brain

- Bessel van der Kolk’s resources: https://www.besselvanderkolk.com/resources/the-body-keeps-the-score

Videos

- UK Trauma Council – Childhood Trauma and the Brain: https://uktraumacouncil.org/resources/childhood-trauma-and-the-brain?cn-reloaded=1

- Trauma Responses (psychoeducation): https://youtu.be/Ys5ywa95x2E

Leave a Reply