Many people come to therapy believing they’re “just bad at communication.”

They may have tried to speak up and frozen; explained themselves and still felt misunderstood; or had feedback land badly, conflict spiral, or relationships drift apart quietly.

And somewhere along the way, they’ve come to the conclusion that the problem must be them.

From a therapeutic perspective, I often see something very different.

Most people aren’t bad at communication at all. They’re actually very good at communicating in ways that once helped them cope, stay connected, or avoid harm. What gets labelled as a “communication problem” is often a protective strategy. One that made sense in the context it developed in, even if it’s now causing friction or exhaustion.

Communication is not just about words. It’s shaped by tone, body language, pacing, timing, emotional history, and what feels safe enough in the moment. It’s influenced by upbringing, culture, relationships, power dynamics, stress, anxiety, and previous hurt. And it’s always happening in a relational field, not in a vacuum.

This post explores communication styles, how miscommunication might show up, why receiving (and giving!) feedback can feel like such a challenge, and how therapy can provide a helpful base to start playing with communication.

As you read this post, please remember: Awareness usually comes before improvement, and self-understanding is almost always a more sustainable starting point than self-criticism.

Communication Styles: Adaptive, Not Fixed

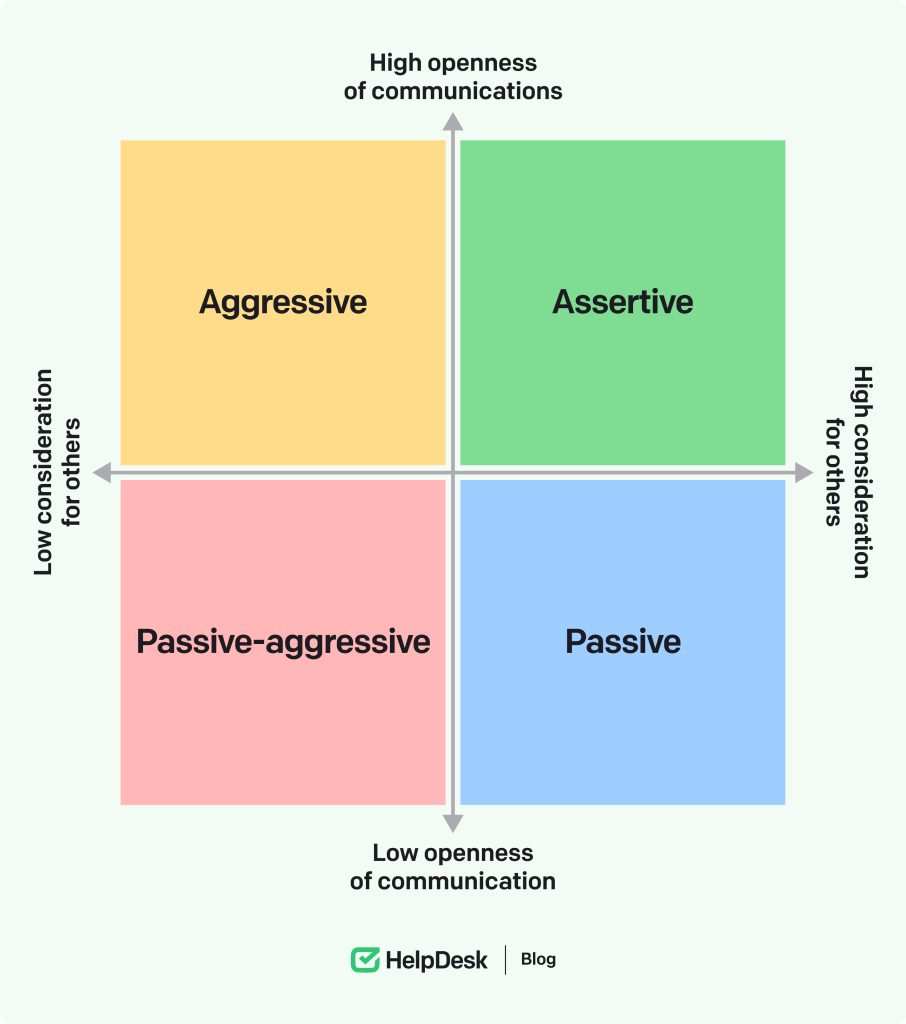

You may have heard of the four commonly described communication styles:

- Passive – holding back needs or feelings to preserve harmony or avoid conflict

- Aggressive – expressing needs forcefully, sometimes at the expense of others

- Passive-aggressive – expressing hurt indirectly

- Assertive – expressing thoughts, feelings, and boundaries clearly while respecting both yourself and others

These categories can be useful shorthand, but what’s important to know is this:

They are not fixed personality traits.

Most of us move between styles depending on context. The same person may be assertive at work, passive in their family, and aggressive when they feel cornered in a romantic relationship. That variability isn’t a flaw, but information.

Often, patterns look something like this:

- When we feel unsafe or insecure, passivity can appear.

- When we feel threatened, aggression may take over.

- When we’re hurt and holding it in, passive-aggressive communication can surface.

- When we feel safe enough, assertiveness becomes more available.

From a therapeutic lens (and particularly from a person-centred, trauma-informed perspective), each of these styles is adaptive. They often developed for good reasons. For someone who grew up in an environment where conflict led to punishment or withdrawal, staying quiet may have been the wisest option available. For someone who had to fight to be heard, forcefulness may have been necessary. For someone who learned that directness wasn’t welcome, indirect expression might have been the only way feelings could leak out at all.

The aim isn’t to label yourself or rush to change. It’s to get curious, and to notice when a certain style shows up, with whom, and under what internal conditions.

Because communication doesn’t start with technique, but with safety.

Why We Miscommunicate (Even When We’re Trying)

One of the reasons communication is so tricky is because we don’t just exchange information, we also interpret it. Constantly.

There’s a helpful TED-Ed video that explains how miscommunication often occurs because people filter language and body language through their own cultural and relational lenses. What feels neutral, caring, or direct to one person may feel dismissive, confrontational, or cold to another.

Tone, facial expression, silence, speed, eye contact—all of these get interpreted through our personal frameworks. And those frameworks are shaped by past experiences, attachment histories, and cultural norms.

This means that misunderstandings aren’t necessarily signs of bad intent or poor skills. Often, they’re signs of difference. Difference in background, expectation, nervous system state, or relational learning.

When you add fear into the mix, things get even more complicated.

Feedback and the Nervous System: Why It’s So Hard

If there’s one area where communication theory tends to fall apart in practice, it’s feedback.

Feedback rarely lands as neutral information. On a nervous-system level, it can register as threat. (Think performance reviews, difficult conversations at work, or moments where someone says, “Can I give you some feedback?”)

Before the content even lands, the body may already be asking:

- Am I about to be rejected?

- Am I in trouble?

- Do I need to defend myself or fix this quickly?

When that happens, people often move into one of two broad responses: performance or self-preservation.

Performance mode might look like:

- Staying agreeable

- Explaining yourself immediately

- Trying to “take it well,” even if you feel small or ashamed

From the outside, this can look like composure or maturity. Internally, it may involve swallowing your experience to keep the relationship intact.

Self-preservation might look like:

- Rejecting the feedback outright

- Becoming emotional because it feels like a personal attack

- Arguing that the other person doesn’t understand or isn’t qualified to comment

From the outside, this can be labelled defensiveness or “being hard to challenge.” Internally, it’s often someone trying very hard not to fall apart.

What often gets missed is that feedback is most workable when there’s enough safety in the relationship to stay present. Without that foundation, even well-intended feedback can overwhelm, shut someone down, or be misread entirely.

To illustrate this: who are you more likely to take feedback from—your best friend, someone you dislike, or a random stranger on the street?

There’s a parenting and teaching philosophy that emphasises “connection before correction.” It recognises that feeling safe, understood, and valued makes someone more receptive to guidance. In my experience, the same applies to adults.

If you’re giving feedback, it can help to:

- Check your agenda beforehand (am I trying to help, or discharge something?)

- Consider how much the other person trusts you

- Build a foundation of care before offering correction

- Be specific and behaviour-focused rather than global

- Explain why and how the feedback might be helpful

And if you’re on the receiving end:

- Allow yourself to pause before responding

- Ground your body before continuing

- Ask for clarification when something feels unclear

- Name if you feel criticised, uncomfortable, or ashamed

Needing time, clarity, or care doesn’t mean you’re being “difficult.” It just means you’re human.

When both people stay engaged, feedback can become something other than a threat. It can even strengthen a relationship.

Disagreement, Rupture, and Repair in Relationships

Many people are very good at understanding their feelings privately, or at explaining them later to someone else. What’s often much harder is saying how someone actually lands with you while you’re with them.

This is where communication becomes deeply relational.

One of the things therapy can offer is a place to practise this safely. For some people, the therapeutic relationship becomes the first space where it’s possible to be angry, hurt, disappointed, or confused with another person without being rejected, dismissed, or met with defensiveness.

In the room, we might gently explore what it’s like to say things like:

- “I felt hurt by that.”

- “I don’t feel understood right now.”

- “I was angry with you.”

- “It felt like you didn’t care.”

And then to stay present long enough to discover that honesty doesn’t have to end the relationship. That disagreement doesn’t automatically equal rupture. And that even when rupture does happen, repair is possible.

Learning that it’s okay to express how you feel—and remain in relationship—can be profoundly confidence-building. It can reshape expectations, soften shame, and expand what feels emotionally possible.

This kind of relational learning doesn’t happen through insight alone. It happens through experience.

Role Play: From Thinking to Feeling It Out Loud

Sometimes, in therapy, we don’t just talk about the hard conversation.

We actually step into it.

Through role play.

Not to perform it or get it right, but to try it on for size. In a room where nothing bad happens if it comes out clumsy, unfinished, or awkward.

What I often notice is how different it feels to say something out loud compared to rehearsing it internally. Someone may start in a familiar narrative—explaining, justifying, circling—and then stop mid-sentence and say, “Oh. I get it now. This is what I always do.”

Something lands in a way that couldn’t have landed in thought alone.

Role play slows the moment down. It makes space for pauses, nervous laughter, emotional surges, uncertainty. It allows us to notice the urge to collapse, placate, over-explain, or go quiet, and to experiment with not doing that.

It can also be a powerful way to practise assertiveness: to feel what it’s like to hold your ground, to stay steady when someone disagrees, and to talk through what comes up afterwards rather than pushing past it.

Sometimes clients play themselves. Other times, I’ll take on a role to model or explore relational dynamics. Either way, it gives us rich, live information that talking about the situation can’t always access.

As a counsellor in Blandford Forum, I really love this intervention. Not because it’s dramatic, but because confidence often grows quietly here. Not because someone was taught what to say, but because they experienced staying present while saying it.

And often the realisation is simple and surprising:

Oh… this isn’t as unbearable as I imagined it would be.

Communication as a Relational Skill

If there’s one thread running through all of this, it’s that communication isn’t just a skill to master. It’s a relational process shaped by safety, history, and emotional context. This is especially true for people who’ve relied on substances or behaviours to cope; in my work as an addiction counsellor, communication difficulties are often less about skill and more about safety.

Improving communication doesn’t usually start with scripts or techniques. It starts with curiosity. With noticing what your system does under pressure. With understanding how your ways of speaking once protected you.

From there, change becomes less about forcing yourself to be different, and more about expanding your capacity to stay present, honest, and connected, even when things feel uncomfortable.

That kind of growth tends to be quieter than people expect, and a lot more sustainable.

Leave a Reply